Edmund Phelps On Innovation, Prosperity, & The Good Life

Edmund Phelps Is The Winner Of The 2006 Nobel Memorial Prize In Economics.

He Is McVickar Professor Emeritus Of Political Economy At Columbia University.

By Aiden Singh, August 5, 2025

Aiden Singh: Philosophy, literature, and the arts, have all explored the idea of the ‘Good Life’ - the question of what constitutes a fulfilling and meaningful life - for ages.

Explorations of it can be found in the works of philosophers like Aristotle, literary figures like Shakespeare, and economists like John Maynard Keynes.

And I’d venture to guess it’s something that appears in the writings and art of every major civilization and that this question was one even early humans grappled with.

In your book Mass Flourishing, you make a connection between the Good Life and economic dynamism - economies characterized by high levels of innovation, rising economic productivity, and rising wages.

How are those two things - the Good Life and economic dynamism - connected?

Edmund Phelps: In Mass Flourishing, I argue that the good economy is the kind of economy offering the Good Life as conceived by Aristotle, which basically amounts to having the freedom and opportunity to pursue creative and meaningful problem solving.

In that regard, economic dynamism refers to the process and effects of individuals actively engaging in creative problem solving within their industry at the foundational level of an economy or the grassroots.

Creativity, when applied toward productive economic ends, directly enriches both the economy and also contributes to a meaningful fulfilling life for the individual contributor.

When individuals pursue fulfillment, purpose, and creativity - central aspects of the Good Life - they naturally produce innovative ideas that drive economic productivity.

One of Bloomberg Businessweek’s Best Books of 2014

One of Financial Times Best Economics Books of 2013

This creates a virtuous cycle. Dynamic economies provide individuals with opportunities to flourish and flourishing individuals fuel further innovation and growth.

Aiden Singh: You see innovation as a form of self-expression, correct? And so, in a sense, stifling innovation stifles self-expression?

Edmund Phelps: That's correct. Innovation basically means creating something new or solving a problem, which I see as central to the human experience. When a person innovates, whether by designing a new tool, launching a start up, or simply finding a better way to do their job, they are giving creative expression to their imagination and individuality. By imagining and creating something new, people reveal a part of who they are.

Besides the benefits to an individual who can express themselves through their work, the general market also benefits from bottom-up innovation.

David Hume said there wouldn't be any progress in the world if it weren't for human creativity.

On the other hand, workers with jobs that consist of repetitive or menial labor, devoid of creativity, ultimately experience a diminished quality of life and a lack of sense of autonomy. So they are not as productive. And we as consumers are unable to reap the benefits of their imaginations.

- - - - - - -

The West’s Golden Age

Aiden Singh: You’ve described the century running from 1870 to 1970 as the West’s Golden Age - a period characterized by high levels of economic innovation, rising labor productivity, and growing wages.

What forces - policy, cultural, historical, or otherwise - came together to produce this Golden Age?

Edmund Phelps: The Golden Age, I think, rose out of a strong cultural shift toward modern values, individualism, vitalism, and creative self-expression, which provided the essential building blocks for domestic dynamism to flourish.

While there wasn't one single policy that led to this shift, what mattered in the end was democratized economic participation where individual workers broadly felt encouraged and empowered to innovate, contribute, and create, solving practical problems in workshops, farms, and factories. Millions of ordinary workers and tinkerers felt empowered to suggest improvements or start enterprises. That widespread engagement was key to sustaining high growth in productivity and wages.

What that means was that places like the United States, for instance, provided relatively open markets and respected rule of law, which meant inventors and entrepreneurs could try new ideas with basic assurances that they would be rewarded by the market and their customers and not exploited or stolen from by copycats and competitors. The framework of property rights, patent laws, and open market participation meant that a person with a good idea had a fighting chance of developing and marketing it.

There were important historical tailwinds as well. The spread of scientific knowledge gave innovation as a concept intellectual legitimacy. It was seen as comparable to ‘scientific progress’ and eventually just progress. Populations were also growing and becoming more urbanized, creating both the demand and the networks for new ideas to circulate and be commercialized. The fact that this era mostly avoided any return to feudal or rigidly traditional systems means that fortunes were constantly changing hands, at least compared to the previous historical eras and could be reallocated to fund new projects instead of hoarded by established interests.

- - - - - - -

Has The West Lost Its Economic Dynamism?

Aiden Singh: You’ve put forward a rather concerning thesis, arguing that economic dynamism in western economies peaked in 1970 and, as a result, these economies have stagnated for over the last five and a half decades. What led you to this conclusion?

Edmund Phelps: The decline stems significantly from the rise of corporatism where entrenched interests limit competitive innovation leading to weaker dynamism and diminished job satisfaction.

In terms of identifying this was in fact a peak, we can see productivity statistics showing a marked slowdown in growth rates around this time, and real wage growth essentially stalled for many workers. Qualitatively, surveys began to show that people were finding less satisfaction in their work. For example, in the United States, job satisfaction has been on a downhill slide since the early 1970s, suggesting the nature of work started to change around that time. I came to conclude that the West lost its innovative mojo around 1970.

Some of my research quantified innovation in novel ways.

Edmund Phelps receiving the 2006 Nobel Prize in Economics.

One approach we used looked at the market valuation of companies relative to their assets, essentially to gauge the expected flow of new ideas. We found that countries with more corporatist arrangements - again, meaning where entrenched interests are protected within a firm - saw significantly lower market values. And even the more open US economy showed a falling ratio consistent with the notion that the pipeline of big new ideas was narrowing after 1970. But as I like to say, when I become pessimistic about America, I think about Europe, and then I feel better about my country.

- - - - - - -

Corporatism

Aiden Singh: One culprit you’ve identified as a cause of this stagnation is ‘corporatism’ and its interest in rent-seeking.

In particular, you’ve argued that innovation in traditional industries (i.e. not including Silicon Valley) has been blocked by this corporatism.

And you’ve contrasted corporatism with what you’ve called the ‘modern values’ of innovation and individual expression.

How has corporatism impeded economic dynamism?

Edmund Phelps: Corporatism, as I briefly hinted before, is an economic model in which established interests such as large firms and governments collaborate closely and take actions aimed at maintaining their positions through rent-seeking and protection rather than fostering genuine innovation and true competition. It has its origins with Mussolini who wanted the state to have more control over firms. Corporatists end up with a clientelist economy where success comes from political connections and deals, not from serving consumers with better products.

In many western countries after 1970, an increasing share of talent and capital went into seeking favorable regulation or tax treatment instead of building the next great industry. The managed economy characteristic of corporatism inevitably struggles to dynamically respond to shifting market forces and consumer demands. A more rigid structure slows the pace of adjustment and limits the scope for experimentation. For example, if you need approval from a consortium of existing companies and unions to start a new venture, as was or may be still is the case in some European economies, you're far less likely to bother.

Firms that exhibit corporatist behavior increasingly choose stability over bold uncertain innovations. Corporatists basically argue that capitalism's market-driven free-for-all is too chaotic. So they organize their structures to insulate themselves from competition. Contrasting sharply with the modern values of dynamism, corporatism sidelines individuality, creative expression, and risk-taking - precisely the cultural ingredients that historically fuelled economic flourishing. Ultimately, corporatist practices erode the foundations of dynamism, curbing both economic growth and meaningful personal fulfilment of workers.

It is never as innovative as an economy based on free enterprise.

- - - - - - -

Government Policy

Aiden Singh: Another factor you’ve identified is government policies aimed at social protection. How have these types of policies impeded innovation?

Edmund Phelps: Many well-intentioned social protection policies often inadvertently reinforce incumbents and entrenched interests, dampening the incentives to compete.

By social protection, I mean things like extensive job security regulations. For instance, if policies make it extraordinarily hard to fire workers, firms become cautious about hiring and experiment less with new ventures since they might be stuck with their workforce even if a project fails. Likewise, workers protected from competition might resist new technologies that could alter their job, slowing the diffusion of innovations. This fosters an environment of status quo thinking where stability and preservation override the impulse to explore new ideas and creative ventures.

Edmund Phelps delivering his Nobel Banquet Speech in 2006.

Once you have robust socialist protection programs, interest group forms to defend them aggressively, sometimes at the expense of broader progress.

Europe, in particular, struggled with this. Attempts at economic reform are accused of threatening social protection even when those changes could spur innovation and ultimately create better jobs. This was also a significant factor in the slowdown in Europe in the eighties.

Aiden Singh: Are there other types of government policy which stifle innovation?

Edmund Phelps: Beyond corporatist social protection per se, there are several policy domains that often unintentionally stifle innovation.

One major culprit is overregulation, which, although sometimes enacted with protective intentions, frequently creates layers of bureaucratic friction that slow the pace at which innovative enterprises can grow and adapt. When the regulatory code swells to tens of thousands of pages, as it has in the United States for instance, it raises the cost and complexity of doing anything new. Small innovators often lack the legal terms to navigate such thickets, so they either don't enter the market or quickly give up.

Tax policies can hinder innovation by either penalizing successful ventures or insufficiently incentivizing risk-taking and entrepreneurial activity. The US tax code has also ballooned to thousands of pages. This complexity often advantages those who can afford expensive tax lawyers established in larger firms and disadvantages smaller companies and entrepreneurs.

Another issue is excessive government capital allocation through grants or spending. A government that's too heavy-handed in directing capital might inadvertently suppress the grassroots bottom-up indigenous innovation that it can't see or measure by a policy. Any policy that privileges incumbents, complicates the market landscape, or restricts competition is likely to hurt or slow innovation.

- - - - - - -

Culture

Aiden Singh: The Good Life, you’ve argued, is characterised by a pursuit of adventure, expanding your horizons, discovering your talents - and all the uncertainty that comes with that.

And you’ve argued that this has been largely lost - replaced with a prioritizing of job security.

Do you think this represents a broad cultural shift in how we view our relationship with work?

Edmund Phelps: One of the biggest factors in our cultural attitudes toward work can be seen in the trauma of the Great Depression, which led to a craving for increased job security. The ideal role after such an intense period of scarcity was to become a company man. These kinds of social and cultural attitudes take a few decades to really set in though.

So the Depression in the 1930’s, arguably, was a big contributor to the loss of dynamism in the seventies. If you think about it, people who grew up in the thirties would have been 40 or so in the seventies - around the peak of their careers. So cultural shifts like this are on a bit of a delay. In 2025, managers in their forties or maybe fifties now grew up in the eighties and nineties.

I think the biggest recent change is new technologies that have made work more physically isolated, especially in the past five years since COVID. Many young people now work from home, which has been endlessly discussed. Whether this trend continues or reverses is, of course, undetermined.

If we think about what is more likely to provide adventure, autonomy, and fulfilling experiences, I can't imagine it’s sitting in front of your laptop at home all day. It's also probably not sitting in an office doing the same work, which is part of what started to numb people in the seventies.

Aiden Singh: You’ve said that the root of the Golden Age of economic dynamism was not capitalism, but rather the people engaged in economic activity. Capitalism supported and enabled it, but at its heart was the spirit of the age.

In contrast, you’ve argued that the workforce today can act as an obstacle to innovation. How so?

Edmund Phelps: When I emphasize the people over the particular economic system, I mean that the mindset and values of the workforce are crucial. Innovation relies heavily on a cultural willingness to embrace change, take risks, and challenge the status quo. In the Golden Age, the workforce largely possessed modern values. They were eager to try new things, to improve their lot, to take initiative.

Hayek talks about how even the lowest ranking employees possess unique knowledge about their job. This can be a valuable source of innovation and problem solving for specific industries, which benefit us all when implemented and allow us to reward those low-ranking employees in an outsized way if they contribute something worthwhile.

In entrenched industries, regulatory capture and extensive lobbying efforts protect incumbents from newcomers and resist innovations that might disrupt their current jobs. If every existing job and enterprise is protected, how can an innovator break into the market with a better product?

In a dynamic economy, workers are partners in innovation. In a stagnating economy, they are told to believe that innovation is a threat, instead of being brought along and retrained to themselves become the new workforce, to assist with the next stage of technological development.

- - - - - - -

A Loss of Good Jobs

Aiden Singh: One of the consequences of this economic stagnation you’ve identified is wages growing slowly and a loss of good rewarding jobs.

By ‘good jobs’ you mean jobs which facilitate the Good Life; jobs which are fulfilling and rewarding and provide an opportunity for personal improvement - not just good salaries.

How does a loss of economic dynamism reduce the availability of such jobs?

Edmund Phelps: In a dynamic economy, new sectors are popping up. Think of the automobile industry in the early twentieth century or the tech sector more recently. And with them come roles that are novel, challenging, and often empowering to those who fill those roles.

In contrast, stagnation confines workers increasingly to repetitive, uninspired tasks, intensifying burnout and dissatisfaction. And governments can legislate or firms can demand from the top down.

In innovation driven economies, growth tends to be broad-based in its benefits when it is truly grassroots. In a dynamic economy, new industries and enterprises create demand for new skills and labor, often lifting the income and opportunities of those who participate and not just their founders. For example, think of how the growth of the automotive industry in the early twentieth century or the I.T. industry more recently created millions of engaging jobs. When such expansions occur, wages rise more generally and unemployment falls, which naturally can reduce income gaps. In contrast, in a stagnant economy, wealth often accumulates to those at the top and the top tends to congeal around older industries.

When innovation slows, innovative industries lean toward standardization, efficiency at all costs, and cost cutting measures that minimize the room for fulfilling or creative roles. Stagnant innovation also leads to slower productivity growth, which puts a drag on wages and career progression.

Even more than the particular wage, a good job, in my definition, offers a sense of advancement and achievement, solving a real problem. But if companies aren't growing themselves, there's less room for employees to grow too. Workers can’t take on new responsibilities, learn cutting edge skills, or rise rapidly because the whole economic pie isn't expanding as it once did.

We've seen this in the data since the 1970s. Real wage gains for the average worker have been meager, and that has been combined with a lack of breakthroughs that would boost labor demand.

There's also a mismatch of expectations. We raised generations on the promise of the Good Life through work. Follow your passion. If you studied and worked hard, you'd find work that is not only decently paid but engaging. Even a highly-paid job could be mind-numbing with no sense of contribution to something larger. When the economic frontier stops advancing, work loses much of its spark. Without that spark, both personal fulfillment and broad-based prosperity suffer.

- - - - - - -

Solutions

Aiden Singh: So how do we fix this loss of economic dynamism? Can we bring about a new Golden Age?

Edmund Phelps: It takes place at every level of business, including the lowest or really the foundational roles. On the policy front, we need to roll back the corporatist aspects that have built up in the economy. This could involve simplifying regulation and the tax code to level the playing field for newcomers. It's absurd to have a tax code thousands of pages long. Only incumbents benefit from that complexity.

We should scrutinize unnecessary rules that protect established firms. In short, make room for the new. Ensure that a brilliant young person with a business idea doesn't feel crushed by bureaucracy or excluded by insider networks.

Another possibility is to redirect incentives toward innovation. Governments can, for instance, support research and development in nascent fields with long-term oriented programs, like funding basic research, which the private sector may under provide if profitability is uncertain.

Overall, I remain optimistic about the economic future of the West and the world in general. I believe human creativity is the most powerful force in the world when allowed to effectively flourish.

- - - - - - -

Wealth Inequality

Aiden Singh: You’ve argued that innovation is a solution to rising wealth inequality. This is a very different idea than using taxation to reduce inequality. How might innovation reduce inequality?

Edmund Phelps: The term inequality is thrown around quite frequently. It's true that innovation can create some winners who become very rich. But if the overall pie grows and new entrants keep coming, the relative disparities can lessen. Innovation is an equalizer over time. It disrupts old structures.

Redistribution through taxes has its place, but it treats symptoms.

Innovation goes at the root of creating wealth and opportunity, ideally pulling up those at the bottom through meaningful and rewarding participation in economic growth. What is under-discussed, in my opinion, is the concept of inter-generational inequality: it's equally important that future generations be at least as well off as current generations. The opposite would be a very worrying trend.

I formulated the golden rule of capital formation in the early 1960s. Very briefly, it refers to the optimal savings rate as that which sustains the highest possible steady state level of consumption per person over time. Each generation should invest a share of income for the benefit of future generations that it would have wanted previous generations to invest for its own benefit. Thus, the consumption level should be the same for all generations. If a generation fails to invest at this level, the next generation will experience a reduction in spending power.

- - - - - - -

AI & Robotics

Aiden Singh: If we view good jobs - fulfilling jobs which provide an opportunity for self-improvement - as enabling the Good Life, how concerned should we be about AI and robotics and their potential effects on the nature of work and innovation? Should we be worried about life rendered purposeless by a loss of work? Or should we view them as potentially positive forces?

Edmund Phelps: Historically, automation and technology in general has indeed disrupted employment.

However, in the long run, it also creates new kinds of work and often raises living standards. Although advanced robots and AI may temporarily put downward pressure on some wages or displace certain tasks, they will also boost productivity and profits, which tends to spur new investment and eventually create other jobs. High profits from automation lead to business expansion, which can push labor demand back up.

While I don't think life will become purposeless for everyone, there is a real chance that specific industries may be left behind in a rapid transition. There will certainly be changes.

We might need new policies, possibly even ideas like a tax on robotic labor income as some have proposed, to fund worker retraining or adjustment assistance. We will need a renewed emphasis on life-long learning so that people can smoothly move into new types of jobs that AI cannot do. If some current jobs are automated, new kinds of work will be created in areas we can't yet predict.

- - - - - - -

The Good Life & Edmund Phelps

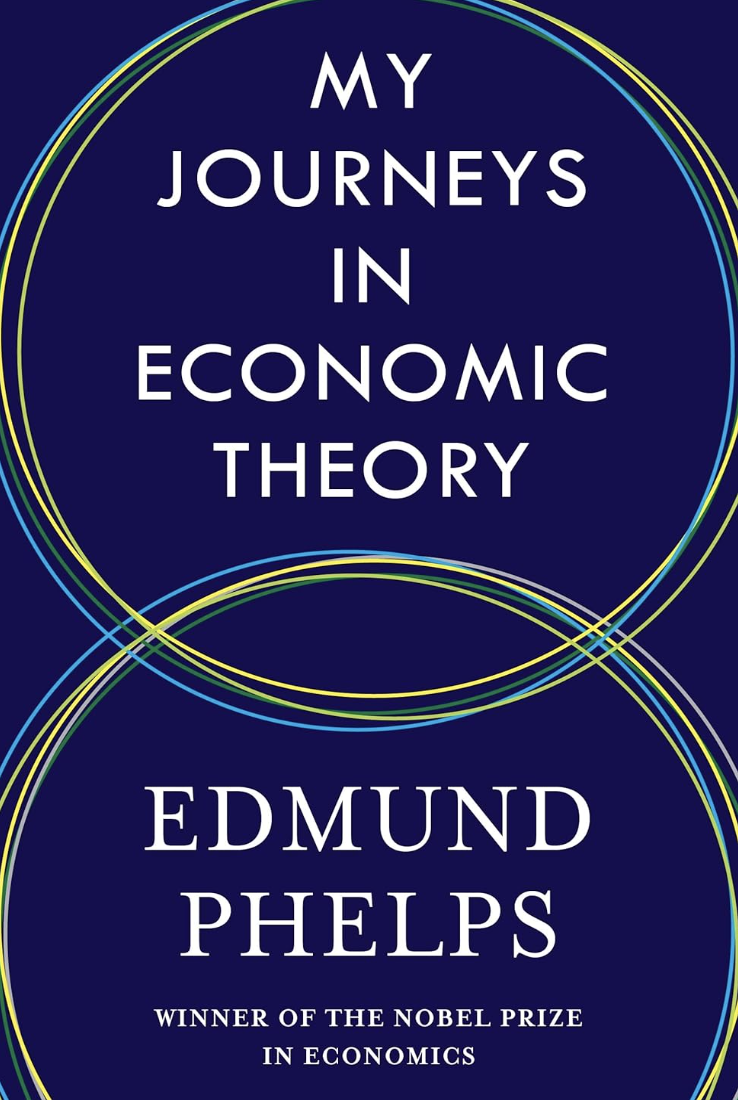

Aiden Singh: In 2023 you published a book called My Journeys in Economic Theory. In the book, you discuss your career in economics, the intellectual debates you’ve been a part of, and your relationships with other leading economic thinkers.

Can you share with our readers how your own career and personal experiences have shaped your views on the relationship between labor, innovation, and prosperity?

Edmund Phelps: Starting in the 1960s, as I worked on issues of unemployment across various countries, I observed how cultural differences in workplaces, say, between the US and Europe affected economic outcomes. Conversations with Jean Paul Fitoussi deepened my perspective on the relationship between policy and social well-being.

A Best Book in Economics for 2023. - Martin Wolf, Financial Times

Likewise, my interactions with John Rawls when he was my office neighbor significantly shaped my thinking about economic justice.

Later on, I turned explicitly to the question of work's meaning. My book, Rewarding Work, came out of concern that many jobs were disheartening or low paying, and it explored how we can restore dignity and incentive for workers at the bottom. Proposing wage subsidies was controversial, but it seemed evident that people flourish when they can participate in work and support themselves. If you mis-manage an economy, you rob workers of opportunities and agency.

Interacting with other thinkers also influenced me. Conversations with colleagues like Roman Frydman, with whom I cofounded the Center on Capitalism & Society, or with critics of my work forced me to sharpen the idea that innovation and inclusion go hand in hand.

I often found myself defending the view that capitalism's success should be judged not solely by GDP, but by the extent to which it engages the whole population in its dynamism. My debates over the years with both those who agreed and those who critiqued me consistently brought me back to this point. Aside from material benefits, if workers lead unfulfilled lives, it isn't real prosperity.

Aiden Singh: So has Edmund Phelps lived the Good Life?

Edmund Phelps: I certainly consider myself very fortunate.

My sixty years of contributing to economics, whether through academic work, teaching, or directing the Center on Capitalism & Society, have been an immense joy.

Equally so is my life with my wonderful wife, Viviana, our family, and our many friends around the world.

I had a good education, abilities, opportunities, and connections.

I was very fortunate.

Edmund Phelps with his wife Viviana During A 2006 Dinner In Honor Of Nobel Laureates.

——————